Part II: The Business

JM: What does your business look like currently?

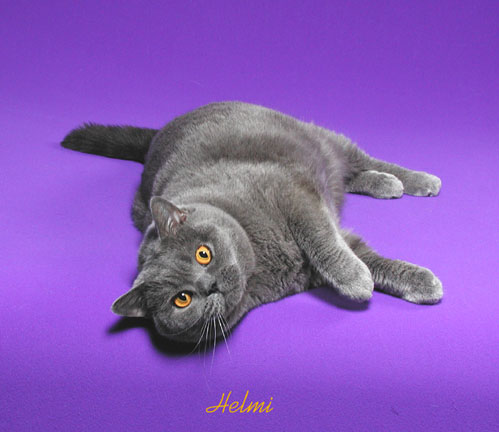

HF: It looks like a marginal enterprise that has been ever so gradually trending toward modest profitability. Although Helmi Flick Cat Photography, now beginning its 6th year in 2006, keeps both Ken and me busy, it has yet to yield the income that either one of us made during our peak years of corporate servitude . . . and nowhere near the leisure time either. Certainly not enough for either of us to have a “day job.”

I’m sure a hotshot MBA could review our business model and find lots of ways for us to expand our revenue streams and increase our income. Clearly, we have not been as resourceful nor as aggressive as we might be in exploring and exploiting the sales potential of our stock photography. At the same time, ironically, it’s clear to us that this is the only aspect of our business with growth potential.

I say that because, as we see it, there are only two basic sources of revenue open to us: first, there’s the income we derive from cat owners for photographing their cats, and second, the income we get from publishers from the sale of the stock images we have amassed. Actually, a third potential income source would be sales of products based on our cat images that we might create ourselves and self-publish, such as calendars, note cards or books. But publishing is another business entirely. First you have to finance a substantial production run to get your unit cost down to a point with some profit potential. Then, to move this costly inventory, you have to distribute your products to retailers or sell them directly, and either of those marketing strategies is an enterprise in itself.

It seems to us that, for the most part, we are already maximizing the income we can expect to get from cat owners for our photography services. And I say that for two reasons involving time and money. Because I was shooting digital from the very beginning of this career, and wasn’t that good back then, I made it my practice early on, not to deliver proofs, only images that I had retouched to correct technical shortcomings or aesthetic flaws. I wanted to make each image my customers chose (during a post-shoot review on a monitor) the best it could be. Digital image editing allows me to do this far more efficiently than it was done in the darkroom days of film, but it’s still a time-consuming process that, to this day, fills most of my time at home when I’m not on the road, shooting at a cat show. I soon found that I could take on no more than one cat show per month and still keep up with my deliveries to customers. And more recently, as my reputation has grown and the volume of business we do at each show has expanded, even that one-show-per-month formula is generating more retouching work than I can deliver on a timely basis.

In a service business such as this, when there is a greater demand for your work than you can accommodate, the obvious solution is to raise your prices. Unfortunately, after several price increases over the years and a couple of reductions in the quantity of product we deliver, that is no longer an option that is open to us. Among the customers in our primary market, the cat breeders and pet owners who exhibit their (mostly purebred) cats at cat shows, there is a market expectation of what a photo session should cost. Our reputation for quality enables us to price our photo sessions at the upper end of this range, causing our customers to spend more on their cats for a session with us than they would spend on a session for themselves at Glamour Shots. Even so, we could never make it on these session fees alone, given the retouching work on the back end that is part of what we deliver.

If we raised our session fees to a level beyond what our cat show customers expect to pay, we might be able to generate the same revenue from fewer photo sessions. This would reduce my retouching workload, which would be a relief, but it would also reduce our chances of attracting customers, some of whom will inevitably have those exceptionally nice cats that we would really like to add to our stock image library. And we need those images of great cats because those are the shots we can resell to publishers, which is a critical revenue stream for profitability in this business. In fact, the only way we can rationalize the paltry profits from cat show photography – which absorbs the great majority of our time -- is to regard this aspect of our business as “image acquisition.” Viewed in that light, at least we’re way ahead of wildlife photographers, for whom acquiring images is their major business expense. Our safaris to cat shows may not make us a lot of money, but at least they pay their own way.

JM: Where do the main sources of income come from?

HF: Our accounting practices are so unsophisticated that we don’t even have a Quicken pie chart to reference in addressing this question. So, we reviewed our numbers for last year (2005) to answer this question and they broke down about like this:

Cat Show Photography: 70%

Private (Studio or Location) Photo Sessions: 4%

Stock Image Sales: 18%

Graphic Design (Custom Posters, Ads, Business Cards): 8%

We knew, intuitively, that there was much room for improvement in our stock image sales, but seeing the percentage of our income this category currently provides, it is clear that we need to double or triple that percentage. Ideally, at this point, stock sales should be yielding as much of our income as cat show photography. And since the two of us are now in our 60s, we will soon approach the time when we’ll want to be working far less, cutting down our shooting on the show circuit, and instead have our stock image library be working for us with greatly increased sales.

JM: As you mention on your website, you have extensive experience outside of the photographic world. What pieces do you feel were necessary in aiding you in your jump to the photographic one?

HF: An affinity for cats.

A desire to express that affinity and share it with others.

A talent for, and some formal training in, the visual arts.

A husband/business partner/fellow cat lover who could guide and assist me in the basics of studio photography.

Enough of the soul-sapping Dilbert existence of a corporate drone in my last job to propel me toward the perilous adventure of self-employment.

A “no fear” approach to trying new things that enables me to “just go for it.”

JM: When you first decided to go full time, what sort of business plan did you develop in order to insure that you would be able to afford to keep your standard of living?

“Business plan?” Yeah, we’ve heard of those. Seriously, that question presumes a greater degree of business acumen, financial discipline and just plain planning than we collectively possess. This is where that “just go for it” approach is, admittedly, a failing, but we have to plead “guilty” on this count. Perhaps that kind of structured thinking would have been essential had it not been for a small inheritance that was sufficient to subsidize our struggling startup during its first couple of years of penurious profitability. But it’s far more likely that, without that financial aid, we could never have survived those first lean years. As far as keeping our standard of living during the transition, we didn’t. But we’re looking forward to the day we get back up there.

JM: What advice do you have for people in terms of developing a successful financial strategy for running a photographic business?

HF: We’re hardly the “gurus” to ask about financial strategies, for the reasons mentioned above. But it would help to have a substantial nest egg going in, or a spouse or partner with a “real job” and income sufficient to bridge your business’s journey to self-sustaining status. Or at least, more of a head for the hard core basics of business than Ken and I have between us.

JM: What experience do you have selling stock photography, if any?

HF: We have sold our images to publishers of cat books and cat magazines as well as note cards and even checks, but we cannot claim to have yet marketed our work aggressively. Except for initiating contact with a couple of U.S. cat magazines, all other sales – in the U.S. and abroad – have come from referrals or direct inquiry from the client companies.

JM: What advice do you have for people who are trying to get into stock?

HF: Do what we have been remiss in doing thus far: actively research the companies that are potential buyers of your type of imagery and do whatever it takes to make them aware of your work and interested in doing business with you. If that sounds like totally generic, common sense advice, keep in mind that we are only speaking from experience that, for the most part, we have yet to acquire ourselves.

JM: How did you break into the show circuit?

HF: I described earlier, how I secured my very first gig as a Cat Show Photographer, but it is important to note that the contacts which made this possible were formed as a result of Ken and me having shown our own cats for a year or so before that. If it is your ambition to become a cat show (or dog show) photographer, I believe it’s essential to immerse yourself in this milieu to see how it works and learn about it from what will be your customer’s side of things. Additionally, the contacts you will make during this exploratory period will facilitate your entry into this world as a “show photographer.”

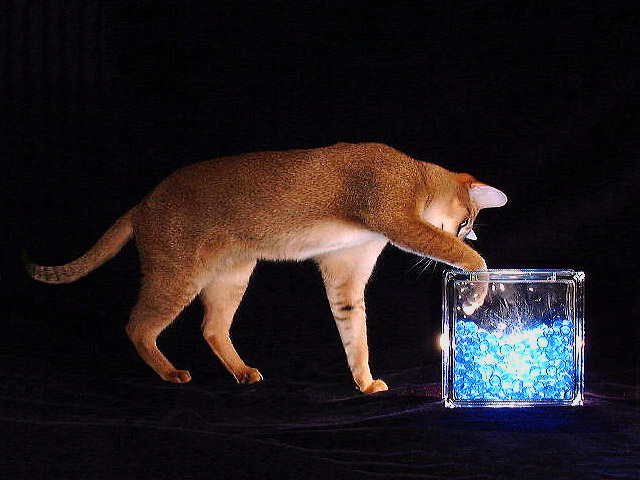

And it almost goes without saying, but if you want to specialize in pet photography – whether it’s cats or dogs, or even birds or reptiles – pick the category of pet with which you have a strong affinity. Animals of most any kind are among the most challenging of photographic subjects, and to choose to shoot a species for which you do not have a deeply felt resonance is to invite frequent and intense frustration, or at least the absence of passion and aspiration. For example, we have shot dogs on occasion, always at the request of our cat-owning customers who have dogs, too. And we have found them far more cooperative, ready to please and easy to pose. But while we admire certain breeds and enjoy their occasional company, Ken and I are not “dog people.” So, even though they are easier to photograph, and even though the typical style of dog show photography is far less demanding (aesthetically, it’s closer to passport portraiture), and far more lucrative, we have never felt that it was right for us.

JM: How did you first start getting your work published?

HF: This was a bit more of a challenge for me than it would typically be for a beginning professional photographer. Everyone starts their photography career as an unknown with only the beginnings of a collection of images to show and sell, no established contacts to submit their work to, and only the vaguest notions of how to acquire them. Beyond these traditional obstacles, I was shooting for the first 2½ years with a 3MP point-and-shoot camera, and this puny resolution created an obvious bias among publishers who were still very much accustomed to working with film.

The most high profile market for cat photos in the U.S. was, and still is, Cat Fancy magazine, so I began submitting my work to them. We were still in the dawn of the digital era in 2001 and even though Cat Fancy had for some time been using electronic publishing processes to assemble their magazine, the editorial staff still insisted that all images be submitted to them as slides. This required me to spend $18 each to convert my digital files to 35mm transparencies, which, if they were chosen for publication, would be converted back to digital files. To me, the insanity of the magazine’s digital-to-analog-and-back-to-digital practice was only exceeded by the economic insanity on my part of spending $18 an image for maybe one chance in ten that it would be published and earn me a $50 usage fee for an inside partial page.

But when the magazine relaxed and began accepting digital image files on CD, I began submitting my work and seeing it published more frequently. In the May, 2003 issue, I was proud to see my first full-page image published. And prouder still to note that this head shot, judicially scaled up from 3MP, was as crisp looking as any other image in that issue. So it came as a surprise when word got back to me a while later that the then current editor of Cat Fancy had told another staff member that I would never have a cover of the magazine while he was its editor.

Fortunately for me, events conspired to change his stand on this matter. For one thing, when I moved up to a 5MP camera, my work became a stronger candidate for cover consideration. But it was only after a staff change in the personnel doing the considering that my images began to be judged on their own merit, without the obstacle of a film vs. digital prejudice.

And, beginning with my first Cat Fancy cover in the March 2004 issue, I managed to get half of the magazine’s covers for the rest of that year. It was a delicious irony that two of these cover images had been shot with my old 3MP Olympus C-3030. I believe there are a couple of points to be taken from this turn of events by those who are aspiring to break into professional photography. First, you don’t need cutting edge, high-end equipment to do good, saleable work .

And, equally important, no matter how good your work, the right contacts are critical. You need

your work to be seen by those who will be receptive to giving it a fair appraisal based purely on the quality of your images and their relevance to the publisher’s editorial needs.

Along the way since those early days courting Cat Fancy, I’ve sold my images to other cat magazines, here in the U.S. and around the world, as well as to publishers of cat books in several countries. In every case, these sales initiated with publishers contacting me after visiting my website. So that’s a sales tool that I regard as indispensable in today’s market and far and away the most economical way to give your work broad exposure.

You can view more of Helmi Flick's work at

http://www.webphotoforum.com/artist.asp?aID=1677 You can also visit her home page at

http://www.helmiflick.com